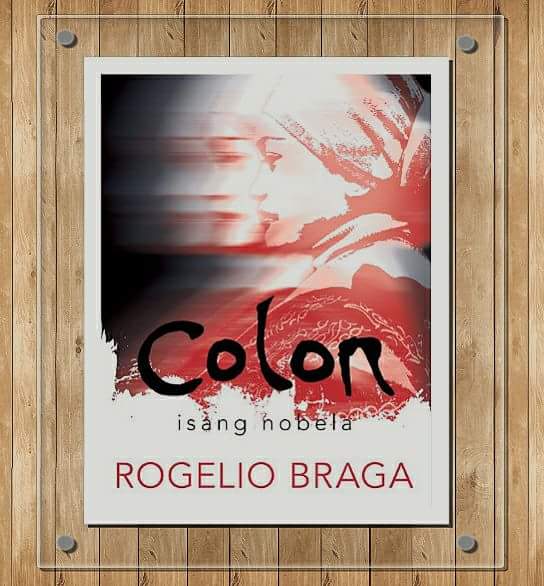

Braga’s literature is free and undaunted. He has no qualms in making his central character “boring” because he has that rare talent of making boring fashionable. He did it in Colon, a novel written in the Filipino language and follows the life of the woman protagonist Blesilda.

Blesilda is an unusual character in an era where the young and wild are favored. Blesida, in all her semi-conservative and shielded life, is the lady who can blend it with any crowd. Pia Wurtzbach she’s not. Blesilda is a regular woman: works, goes home, works, goes home. Her life is a boring routine. But out of this ordinary life began a quest for Blesilda’s identity and her coming to terms with her past that also led to many questions, some answered, others left hanging.

It will be too much to write about the rest of the characters of this book because that will kill the colorful details that Braga brought to life in Colon. But take note of Aldo because his presence (and absence) in the whole duration of the book is essential in the story’s plot.

What most people do not know is that a writer’s job is not only limited to whipping up stories from make-believe characters and writing about imaginary creatures, wizards and witches. Crucial to the work production of a writer is good, solid research and that is evident in Braga’s Colon. I can tell because I’m a Cebuano who knows what Braga wrote about: from the Mactan Cebu International Airport to Lincoln Street of Carbon Market to the road that leads to the University of San Carlos Talamban Campus.

He learned Bisaya, lived in the town of Compostela (around 32 kilometers from Cebu City), and walked around Colon and the downtown area more than 100 times.

I read this book with difficulty on two levels:

(1) It was a challenge to read the first three chapters of this book as a person with very little knowledge about the war in Mindanao. I realized it was a subject not discussed in school almost in the same level as Marcos and Martial Law; and

(2) The last time I read a Tagalog novel was in high school, about 14 years ago, and it was one of those pocketbooks featuring a landed hunk rescuing a poor damsel in distress. Although Tagalog is my second language, reading a Tagalog nobela is different from speaking Tagalog. So it took some time to finish this book.

Braga’s talent to write and to weave historical facts along with a social commentary made me spend hours of purring over the pages of this book. I read and reread chapters and by the end of the fifth, I was convinced it was time to give Tagalog writing a chance (or at least read more books in the language).

Braga is a rare gem in a sea of writers who aim to please a crowd. Braga is no crowd pleaser. He does not conform. He lives with his stories so his stories live with him.

I was enlightened and curious after reading this book because unlike other stories, it ends with a question: How do I move forward from here?

I always believe that the real value of a book is defined by its ability to awaken people’s tired and non-thinking brains; to create venues for healthy discussions; and to encourage readers to go ahead and read some more.

Braga hit all three.

His storytelling is powerful that his book was able to convince my children’s Ate Joy to read again.

I will forever be grateful to the Cebu Literary Festival for serving as that platform to meet Braga and be introduced to his literature.

When I grow up, I want to be like you Ogie.